By Anne Queenan

As the towboats and barges make their way back up the Mississippi River, the 2017 season of commercial navigation begins.

Barge on Lake Pepin, Pool 4 - Photo by Becky Schultz

In addition to the usual navigational and dredging activities related to keeping the nine foot wide channel open, this season on Lake Pepin, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will begin studying closely how and if there's a beneficial use of the sand and sediment it has been dredging and storing - one that would actually help the habitat and water quality at the upper end of the lake. Possibilities under consideration include: dredging backwaters to increase the depths needed for overwintering fish; constructing islands and land extensions for increased vegetation and diversified habitat - under the water, and on the islands themselves.

Sedimentation at the Head of Lake Pepin - Photo by David Meixner

"We're in the initial stages of this. But, we've made the determination that there is a federal interest, which means we can get some funds to study this," said Nate Campbell, Project Manager from the St. Paul District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. These funds have already been allocated for the implementation of this study. Once given the green light, $200,000 is available for the first year and an additional $250,000 to complete the study. The Corps is waiting to make sure all partners are on board with clear expectations and commitment of the objectives, and scope of the study. "What we want to look at is if there is way to use the material from either downstream in lower pool 4, or perhaps upstream, to build some kind of an island, if we find it's feasible to transport that material to the head of Lake Pepin," said Jon Hendrickson, the Corp's Ecosystem Hydraulic Engineer.

Now, let's address some questions:

Who is involved and how?

Why consider a restoration project in Upper Lake Pepin?

What is a feasibility study and why is it needed?

What are the constraints and risks at hand?

Who is involved?

To date, the Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance (LPLA), Audubon Minnesota, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are partners in this study. Rylee Main, Executive Director of the Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance, and Matt Anderson, former Executive Director of Audubon Minnesota, submitted an official proposal in November, 2015 to inquire if there is a federal interest to study and plan for a restoration project at the head of Lake Pepin, beneficially using the sediment dredged by the Corps for ecological restorative purposes. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officially approved and recommended to proceed with feasibility planning on June 29, 2016 through the Continuing Authorities Program, Section 204 (CAP 204). A large part of the work under consideration requires the permission of the Wisconsin DNR, an important stakeholder and potential sponsor. Recently, the Wisconsin DNR has stated interest in determining the feasibility of establishing a project under this program, assuming a range of conditions are met. If the study supports the Wisconsin DNR's goals and objectives and has support from the public, they would also have interest in becoming the non-federal sponsor of the project.

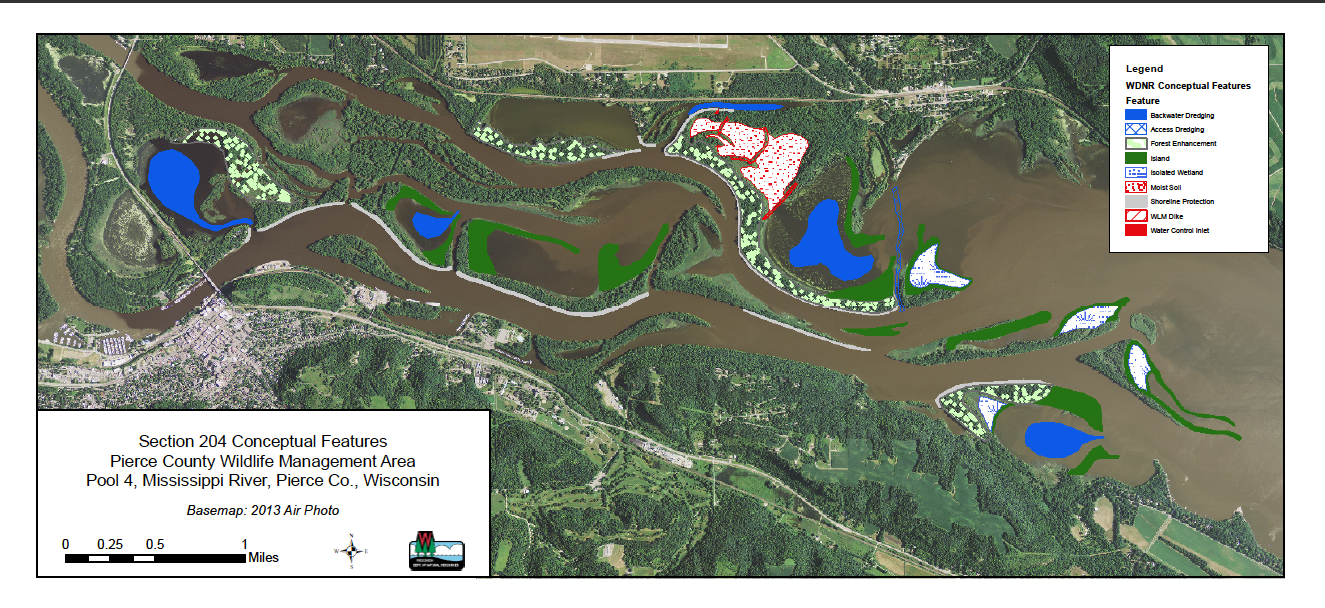

Meanwhile, two sets of concept plans have been designed for this area: one by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, which LPLA and Audubon have been using as an example of what the project might look like in Upper Lake Pepin; and one by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, focusing on their goals and objectives. Islands in the open bodies of water, as well as deeper pools of protected backwaters are included in the first, whereas the Wisconsin DNR's focus is prioritized on backwater areas within Wisconsin. Both will be taken into consideration. The actual process of the study itself, however, will help determine and design where the best locations would be for the most habitat benefit and water quality impact.

Why Consider a Restoration Project in Upper Lake Pepin?

As many who follow the conditions of the Mississippi River understand, multiple ecological concerns demand we pay heed to restorative efforts. Thirteen of them are detailed in a letter of resolution, authored by LPLA and Audubon MN, describing the importance of habitat and water quality improvements in Lake Pepin - which is now supported by two counties in Wisconsin, seven towns and villages, four organizations associated with Lake Pepin, and many local residents. U.S. Representative Jason Lewis has also issued a letter of support for this project and is committed to sustaining the health of the lake through continued conversations with the Corps of Engineers.

Some key ecological considerations at the head of the lake:

- Continued sedimentation and sediment re-suspension

- Changes in floodplain connectivity

- Loss of aquatic vegetation

- Lack of protected wetlands and aquatic areas

- Degradation of habitat for migrating waterfowl and other species

- Loss of aquatic plant coverage and bathymetric diversity (varying depths)

- Loss of depth diversity affecting backwater fish species

Forty percent of North America's migratory birds use the Mississippi River as a flyway to stop and refuel along the journey to their wintering grounds. Among them, the Common Merganser has come to depend on Lake Pepin as a critical source of feeding. The open water expanses of this natural lake are unique. In the late fall, mergansers feed heavily on the abundant schools of shad and shiners that inhabit this large, open freshwater expanse. The lake can provide ideal habitat for these pelagic fish.

Common Merganser, female, on Lake Pepin - Photo by David Meixner

Common Mergansers and other fish-diving waterfowl gorge in Lake Pepin by the thousands, reports Audubon Minnesota. Sustaining quality habitat here is vital. It is deemed an Important Bird Area to Audubon, serving 82 species of spring and fall migratory birds considered to be in greatest conservation need. It is also home to more than 300 American Bald Eagles during the winter. Audubon is interested in doing what is possible to improve water quality and habitat for birds and other wildlife here.

"The best thing we could do is reduce sediment coming in to Lake Pepin. However, since we can't control that, at least Audubon can't, we can do some improvements to habitat in the upper end of Pepin. If the project increases the extent of floodplain forest with a diversity of tree species, and provides some areas with clearer, vegetated wetlands, there will be better habitat than currently exists," said Tim Schlagenhaft, Upper Mississippi River Program Manager for Audubon MN.

In addition to waterfowl, gamefish, including walleye, perch, bluegills and bass, also feed on Lake Pepin's minnows, gizzard shad and emerald shiners. Shad and shiners feed on plankton, which require sunlight to reproduce and thrive in the water column. Some macro invertebrates (insects), another primary source of their diet, also require submerged vegetation as cover and a source of nutrients. By improving conditions needed for insects and smaller fish to feed on - with new submerged vegetation - the project would help restore habitat for this part of the food chain.

This requires enough sunlight to penetrate through the water. When the water is turbid, and the sediment re-suspends and gets stirred up, this vegetation dies off. Lake Pepin has this happening in spades.

Upstream confluence of Minnesota River (R) and St. Croix River (L) - Photo by Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

Approximately 900,000 metric tons of sediment are deposited in Lake Pepin per year. Its level of impairment from sedimentation is well documented, a result of both natural processes and land management decisions upstream.

What can stir up the lake and cause this sediment re-suspension? Increased flows, erosion, boating, and wind-driven wave action across wide open expanses are all factors.

Why do we need a feasibility study and what is involved?

Currently, the lake and backwaters are becoming increasingly shallower. The Wisconsin DNR map below shows various levels of depth in Upper Lake Pepin and its backwaters.

To address the relevance of the feasibility study, a general understanding is needed on how these types of islands, island extensions, and deeper dredging of protected backwater pools could address connectivity of the backwaters from the main body and provide more habitat for fish. The fish that like to overwinter in the backwaters of Lake Pepin, need deeper pools where the temperatures under the ice are slighter warmer than areas with more flow.

A possible scenario: Dredged sediment would be transported and used as a base to construct the land extensions or to build islands in the open water area of Lake Pepin. In the backwater areas, this land could be designed to wrap around proposed deeper dredged pools, in a horse-shoe like fashion. The intent is for the land to help protect and disconnect the deeper pools just enough from the main flow. On top of the base of sediment, a finer substrate would be used as topsoil, in which new trees and diverse habitat could be planted. This finer sand would come from the dredging of the pools there. The pools with varying depths, particularly in a shallow area, will provide more diverse habitat for the fish. They'll possibly also provide improved access for recreational boaters, as a secondary effect.

During LPLA's "Seeing Sediment" Artist Boat Tour last summer, while approaching the Bay City forested area, artists learned about what floodplain forests need to thrive.

LPLA Boat tour nears Bay City floodplain forests - Photo by Anne Queenan

Inundated Floodplain Forest in Bay City, WI - Photo by Stephan Kistler

Tim Schlagenhaft, one of the tour guides, was asked to recap several key points:

Q: How could these islands potentially help to increase the quantity and diversity of trees and plants in a floodplain forest?

A: "Floodplain forests are periodically inundated during high water events. This can be multiple events per year, but is typically during the spring flood and lasting several weeks. Much of the year these forests do not have standing water, other than sloughs and permanently inundated channels. This wet/dry cycle is important to the plants and animals within this system.

We used to have greater diversity of trees/plants before water levels were raised by the locks and dams. When water levels increased, many species, like oak that require slightly drier sites, died out. If islands are built, they could be constructed at a higher elevation that would be suitable to more tree species, so, the project could create more diversity, especially on the constructed islands."

Tim Schlagenhaft of Audubon MN leading discussion on floodplain forests in Upper Lake Pepin - Photo by Anne Queenan

Q: How would an island serve to improve water quality and provide more aquatic plants?

A: "Islands break up the waves from wind and boats and provide protected areas around the island footprint. These areas become less turbid, allowing more light to penetrate to the bottom. Aquatic plants respond to more light and an increase in aquatic plants would be expected, including submerged plants like wild celery and coontail, at least around the islands."

Wild Celery - Photo by University of Wisconsin, La Crosse

In addition, island extensions can reduce the inflow of turbid waters in the area. This helps address not only the wind, but also the flow patterns. This project would likely try to accomplish both.

Some of the island projects can have a "cumulative effect," which results in a more positive impact on a wider swath of acreage from the actual footprint of the island. "For example, an island might cover 5 acres where the sand is placed, but it could affect wind and wave action and have water quality and vegetation benefits up to 100 acres. The feasibility study helps determine total acres affected, which will depend on the project features selected," explains Schlagenhaft. The proposal suggested that 1,000 acres be potentially taken under consideration for the project, however, that will be determined through the study.

What are the constraints and risks at hand?

For this reason and more, the feasibility study is a critical step and a major opportunity to gain relevant input from an experienced team of federal, state, and local experts who will gage all aspects of the best use of these materials. A hydraulic computer model that looks at the flow and movement of water for specified stretches of a large river system will likely be instrumental in assessing how an island might have an impact on breaking up wind fetch, or water action. A wind fetch model also helped downstream in the planning and construction of islands for Lower Pool 9, near Lynxville, Wisconsin, where the goal was to create habitat for the overwintering fish. Similar to Lake Pepin, this involved a big body of water with a good amount of wave action. "It's important to get a handle on how our project might change wave action and flow patterns. We would do the same thing at the head of Lake Pepin," said Jon Hendrickson. In this case, low velocity areas were identified that would be good for overwintering fish. The photos below show Capoli Slough in Pool 9 before the project, in 2011, and after the completion of the project in 2015.

Various ecological restoration projects along the Upper Mississippi River involving island construction and dredging by the Corps will help inform this study. None of these have been quite like Lake Pepin, however. What is more difficult to gage in Upper Lake Pepin, reports Hendrickson, is where and how the continued incoming turbid flow of sediment from the Minnesota River Basin entering Lake Pepin will settle. To be clear, the incoming increased flow of sediment from the Minnesota River Basin will continue until the water upstream is slowed down. This effort would not alleviate that situation. The dynamics at the head of the lake are unique. "Wind fetch is one of the main factors but the inflows from the upstream channels, like the Wisconsin Channel or the main channel, are really important to deal with, too," he said.

In referencing how to assess positioning of islands in an open body of water, Hendrickson added, "We're going to have to pick an area - kind of a target area - to reduce wind-driven wave action and reduce the suspension of sediment. There is guidance on it, for more typical backwaters. I hesitate to say that will apply to the head of Lake Pepin because we have such fine sediments in that area. We might think about it a little bit more," said Hendrickson.

To address questions about the possible risk of unknown effects of shifting sediment deposits, Audubon Minnesota responded:

"The project might not work as well as expected in improving water clarity around the islands due to high ambient turbidity. There would likely be sand brought in from below Lake Pepin to construct the islands that would accelerate the filling of Lake Pepin by a small increment of time. It is Audubon's position that the public / stakeholders should weigh in heavily on this and whether or not the benefits of improved habitat outweigh the negatives of more filling. There would also be lots of barge traffic to move the sand, and equipment to dredge and shape islands that would affect boaters, although this would be temporary and during construction only."

Construction of Islands at Harpers Slough near Lynxville, Wisconsin - Photo by Rylee Main

To put this in perspective, it is a small fraction of sediment in proportion to the amount that settles in the lake every year, explain Hendrickson. According to Rylee Main, "The question for the public is: Do we want improved habitat with a minimal increase in sediment loading from moving the materials, or do we allow continued degraded habitat for a slightly longer lifespan of the lake? This assumes conditions don't change in terms of sediment loading from upstream sources to Lake Pepin."

Additional Constraints

Existing or new knowledge of contaminants in Upper Lake Pepin's history will be critically examined in the first phase of this study. "One of the initial steps in the feasibility study will likely be sediment contaminant sampling," said Schlagenhaft. The results could drastically affect the potential for the project to be implemented.

Another important criteria to assess is whether the sediment/sand being dredged is the quality of substrate needed to construct the island and grow the desired vegetation.

The economics of transporting the sediment from the lower end of the lake to where it is best to construct the restoration project will also be weighed.

Moving the Ecological Needle with the Support of Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance

Today, Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance purports to monitor the conditions at the head of Lake Pepin so meaningful and permanent restoration can be started. "This project is a significant, collaborative step forward to learn how and where we can sustain Lake Pepin's ecosystem and possibly begin restoration of parts of our upper lake," said Scott Jones, President of its Board of Directors. Scott is one of several LPLA founding members and residents of Lake Pepin who have been watching the sediment deposit and flow downstream over the years, forming islands and getting increasingly shallow in spots. "It would be a shame if this beautiful lake turns into nothing but a navigation channel - isn't there something we can do?" asked Marilyn Albrecht, another founding member, eight years ago.

Stay tuned and Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance will listen to your questions and keep you abreast of updates.

Rylee Main leads "Seeing Sediment" Boat Tour with Lake Pepin artists and guests - Photo by Anne Queenan